|

Even though the author (MacDonald wrote the section on Arnaville) deals with the Dornot Bridgehead only as prologue to the Arnaville Bridgehead, his coverage of the units involved is more thorough than that of Cole. The entire section "River Crossing at Arnaville: the story of the 10th and 11th Infantry Regiments, 5th Infantry Division, and Combat Command B, 7th Armored Division, in crossings of the Moselle River at Dornot and Arnaville, France" is on pages 1-99 in four chapters, plus a section on the Order of Battle (pages 96-97, which is especially helpful for identifying which units may have been in the Dornot Bridgehead) and a Bibliographical Note section (pages 98-99).

Charles B. MacDonald's entire first chapter covers "The Gasoline Drought and the Dornot Crossing" on pages 3-39 and includes the following maps and illustrations:

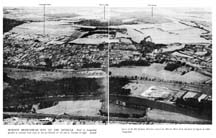

- pages 10-11 Illustration: "Dornot Bridgehead Site on the Moselle"

- page 15 Illustration: "Congestion in Dornot"

- page 18 Illustration: "Approaching the Moselle Under Enemy Fire"

- page 19 Illustration: "River Crossing Near Dornot"

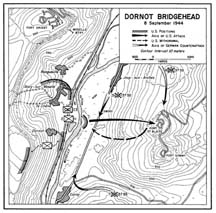

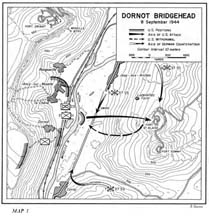

- page 24 Map 1: "Dornot Bridgehead, 8 September 1944"

- page 33 Illustration: "Infantryman at Footbridge Over Railroad"

The Bibliographic Note section includes important notes about Dornot:

- "Because the combat interviews and unit records left a number of major gaps in details of the action, the author conducted several postwar interviews and extensive correspondence with surviving participants. The information thus elicited proved valuable, especially in presenting the confused command picture in the vicinity of Dornot on 7-8 September. In no instance, however, has the historian accepted postwar material as refutation of any fact which can be established from contemporary records. These letters and interviews have been filed with the OCMH." (page 99)

- "Sources for German material were postwar manuscripts prepared by captured German officers; letters, orders, and reports found in an annex to the KTB (War Diary) of Army Group G; and a detailed account of the Dornot action found in war diary pages constituting part of a miscellaneous file of the 2d Battalion, 37th SS Panzer Grenadier Regiment. The postwar manuscripts, prepared under the direction of the Historical Section, U. S. Forces, ETO, and depending almost entirely on the unaided memories of their writers, add immeasurably to knowledge of the enemy operations. MS # B-042 (Krause), of particular value in preparing this study, is detailed and apparently accurate and unbiased. The annexes to the KTB of Army Group G are at a level of command too high to be of much value in a small unit account such as this, but in some instances they were the only German documentary source available. Because few enemy records at a small unit level survived the war, the war diary pages of the 2d Battalion, 37th SS Panzer Grenadier Regiment, constitute an almost unique source. This source was used extensively to provide an enemy account of the Dornot action which is admittedly out of focus with the level of narration of the enemy story in the Arnaville battle, but its intrinsic interest and value were considered sufficient to warrant such irregularity. German manuscripts are to be found in the OCMH files, and official German records are in the German Military Documents Section, Departmental Records Branch, Office of the Adjutant General. Additional material on the enemy side was obtained from G-2 Journals and files of the 5th Infantry and 7th Armored Divisions. Prisoner of war reports, when checked against enemy materials, proved generally accurate." (page 99)

Bibliographic Footnotes about Dornot:

- "The 5th Div story has been reconstructed from the following: 2d Lt F. M. Ludden, Combat Interv 38, Sep 44, including a valuable preliminary narrative, Moselle River Crossing at Arnaville, 8 Sep 44-24 Sep 44 (hereafter cited as Moselle River Crossing). (All combat interviews on the Moselle crossings are by the 3d Information and Historical Service and were conducted in September 44.) See XX Corps, 5th Inf Div, 1103d Engr (C) Gp, 10th Inf and 11th Inf, AAR's and Unit Jnls, Sep 44; Pass in Review—the Fifth Infantry Division in ETO (Atlanta, 1946) (hereafter cited as Fifth Infantry Division); History of the Eleventh United States Infantry Regiment (Baton Rouge, 1947) (hereafter cited as Eleventh Infantry); History of Tenth Infantry Regiment United Slates Army (Harrisburg, 1946) (hereafter cited as Tenth Infantry); Third United States Army After Action Report—1 Aug 44-9 May 45 (hereafter cited as TUSA AAR). See also Intervs with the following: Irwin, 28 Mar and 10 Apr 50; Yuill, 17 Apr 50; Maj Cornelius W. Coghill, Jr. (formerly S-3, 11th Inf), 19 Apr 50; Lt Col Kelley B. Lemmon, Jr., 12 Jul 50; Lemmon and Yuill, 13 Jul 50; Thompson; Morse. Ltr, Lt Col William H. Birdsong (formerly CO, 3d Bn, 11th Inf) to Hist Div, 27 Mar 50." (pages 9, 12)

Maps and Illustrations

|

Page 24: Here is Map No. 1, by R. Hanson. It is the same map as Cole's Map No. 3.

Click on image for full size.

|

Pages 10-11: The"Dornot Bridgehead Site on the Moselle" illustration is the same aerial image used by Cole. But it has different annotation and a caption that adds a lot to the understanding of the crossing.

DORNOT BRIDGEHEAD SITE ON THE MOSELLE. Road in foreground parallel to railroad track leads to Ars-sur-Moselle on left and to Novéant on right. Assault forces of the 5th Infantry Division crossed the Moselle River from top point of lagoon in center foreground.

Click on image for full size.

|

MacDonald's Account of the Dornot Bridgehead

|

MacDonald: XX Corps Approach to Metz - Main Issues

"In general, the XX Corps staff believed the fortified system outmoded, and both the Third Army and XX Corps tended to assume that the Germans would at most fight a delaying action at the Moselle and that the main enemy stand would be made east of the Sarre River behind the Siegfried Line. Apparently on this assumption, virtually no information on the Metz fortifications was transmitted to lower units, not even to regiments." (page 4, with fn 7 "XX Corps G-2 Jnl and File, Sep 44; TUSA G-2 Periodic Rpt, 3 and 8 Sep 44; Interv with Brig Gen John B. Thompson (Ret) (formerly comdr, CCB, 7th Armd Div), 6 Apr 50; Interv with Maj W. W. Morse (formerly S-2, 11th Inf), 19 Apr 50. Unless otherwise indicated, all interviews were conducted by the author in Washington, D. C.")

"Actually, Hitler and his military advisers had no intention of permitting a withdrawal from the Metz-Thionville area; not even so much as retreat behind the Moselle was contemplated, because the Metz fortifications extended west as well as east of the river." (page 4, with fn 8 "Sit Rpt, 4 Sep 44, found in Heeresgruppe B, Ia, Lagebeurteilungen (Army Group B, G-3, Estimates of the Situation), 1944.")

"The American estimate that the Metz forts were outmoded was basically correct, even though the inherent strength of individual fortifications might be obscured by such a generality. While the French had concentrated primarily on the Maginot Line, farther to the east, the Germans after 1940 had given priority to fortifying the Channel coast. Many of the forts even lacked usable guns, ammunition, and fire control apparatus, although those forts subsequently encountered by the southern units of XX Corps were in most cases manned and adequately armed. Over-all consideration might label the fortified system as of World War I vintage, but it would be difficult to convince the individual American soldier who faced the forts in subsequent days that 'Fortress Metz' could have conceivably been made more formidable than it actually was." (page 5)

"The Moselle River itself was a difficult military obstacle. In the area just south of Metz the river averaged approximately a hundred yards in width and six to eight feet in depth with a rate of flow considerably greater than that of other rivers in this part of France. The banks of the river south of Metz were flat and often marshy. Before emerging nearer to Metz into a broad flood plain sometimes reaching a width of four to five miles, the river traversed a deep, relatively narrow valley flanked on east and west by steep, commanding hills. With the advent of the rainy season, the river could be expected to become torrential." (page 5)

6-7 September 1944 - Wednesday-Thursday - Approach to Dornot - Depletion of 23rd Armored Infantry Battalion

|

[6-7 Sep 1944]

"Force I consisted of the following:

Co A, 31st Tk Bn (M [Medium]);

434th Armd FA [Field Artillery] Bn (less Btry C);

2d Plat, Co B, 814th TD Bn (SP [Self-Propelled]);

CCB Hq, atchd trps, and tns [Trains].

Force I was later joined by

the 23d Armd Inf Bn (less Co B) and

Co B (less one plat), 33d Armd Engr Bn.

See CCB, 7th Armd Div, AAR, Sep 44."

(page 6 footnote 10)

|

[6-7 Sep 1944]

"Force II consisted of the following:

31st Tk Bn (M) (less Cos A and D);

Co B, 23d Armd Inf Bn;

1st Plat, Co B, 33d Armd Engr Bn;

Btry C, 434th Armd FA Bn;

3d Plat, Co B, 814th TD Bn.

See CCB, 7th Armd Div, AAR, Sep 44."

(page 6 footnote 11)

|

[6-7 Sep 1944] "... Company B, 23d Armored Infantry Battalion, was directed to bypass the town [Gorze] in an effort to reach the river and make a crossing before daylight. Although the company [B/23] did succeed in reaching a canal which closely paralleled the river, as day broke on 7 September the Germans at Novéant and Arnaville, just south of Novéant, discovered the Americans in between them and saturated the area with fire, causing heavy casualties. The infantry [B/23] finally were withdrawn under cover of fire from tanks and mortars." (page 6)

[6-7 Sep 1944] "In the left column (Force I), where the 23d Armored Infantry Battalion (-) had joined the fire fight west of Gravelotte, the newly arrived unit was ordered to push alone to the river. Utilizing a road through the Bois des Ognons and the Bois des Chevaux in order to avoid the narrow Gravelotte-Ars-sur-Moselle defile, which was covered by enemy defenses, the battalion fought its way under the protection of darkness to reach at 0400 the little village of Dornot, some 300 yards from the river. At daylight the Germans on both sides of the river opened up with small arms and mortar fire, and the guns of Fort Driant, on the heights southwest of Ars-sur-Moselle, west of the river, poured in deadly shellfire. To ease its situation, the battalion cleared a little cluster of houses known as le Chêne, on the river just north of Dornot, from which the fire was particularly heavy. This success was exploited by sending in Company B, 23d Armored Infantry Battalion, from Force II and the remainder of Force I, including Company A, 31st Tank Battalion (Medium), to assist the armored infantry battalion. And none too soon, for the enemy began to launch numerous counterattacks, the most severe of which originated at Ars-sur-Moselle." (pages 6-7)

[7 Sep 1944] "While holding against these enemy counterattacks, the 23d Armored Infantry Battalion utilized its three available assault boats in the afternoon of 7 September in an attempt to put a patrol across the Moselle. Direct machine gun fire from the east bank destroyed two of the boats and killed most of the men, driving the patrol back." (page 7)

[7 Sep 1944] "After detrucking, advance elements of the 11th Combat Team [5th Infantry Division] were meeting slight resistance from German infantry who had not been cleared in the armored advance when word finally reached General Irwin about noon on 7 September that the 5th Division was to pass through the armor and establish a bridgehead. By this time the 11th Infantry was deployed and advancing with two battalions forward in widely separated columns, fighting to reach the Moselle. The [11th] regimental commander, Colonel Yuill, had directed his 3d Battalion on the left to reach the river in the vicinity of Dornot, north of Novéant, and his 1st Battalion to capture Arnaville, south of Novéant. His intention was to cross the Moselle with his 2d Battalion either at Novéant or just north of Arnaville in order to avoid suspected enemy fortifications north of Dornot. As night approached, the 11th Infantry toiled slowly toward the high ground overlooking the river." (page 9)

[7 Sep 1944] "During the afternoon of 7 September, the attempt by the 23d Armored Infantry Battalion to put a patrol across the river at Dornot had given rise to a belief that the armored battalion had already gained a toehold across the Moselle. About 1800, XX Corps told General Irwin to cross the Moselle on the following morning and use the 23d Armored Infantry Battalion to augment his own infantry [5ID]. The crossing was to be made at Dornot." (page 7) -- THIS WAS THE ORDER TO CREATE THE BRIDGEHEAD.

[7 Sep 1944] "By midnight, 7 September, the 1st and 3d Battalions, 11th Infantry, had reached their objectives on the high ground between Arnaville and Dornot. Although the order to cross at Dornot had been protested by Colonel Yuill, the 2d Battalion, 11th Infantry, had been preparing for the assault since nightfall. The 1st Battalion, 11th Infantry, under Maj. Homer C. Ledbetter, was being virtually ignored by the enemy at Arnaville, an indication that the latter offered a more likely crossing spot than did Dornot, where enemy reaction continued to be violent. This was apparently overruled by higher headquarters in view of the concentration of infantry and armor in the vicinity of Dornot. But on the ground there was little co-ordination between this infantry [11IR/5ID] and armor [CCB/7AD]. The 3d Battalion, 11th Infantry, first 5th Division unit to reach the Moselle, was as surprised upon its arrival at Dornot to find CCB as CCB was to see 5th Division troops. Neither had any idea of the other's presence or impending arrival." (page 9)

|

As noted, Col. Yuill who was most familiar with the situation on the ground wanted to make the crossing "either at Novéant or just north of Arnaville in order to avoid suspected enemy fortifications north of Dornot". And as also noted, "the attempt by the 23d Armored Infantry Battalion to put a patrol across the river at Dornot had given rise to a belief that the armored battalion had already gained a toehold across the Moselle."

In fact, Gen. Patton had received this erroneous report of a "toehold" bridgehead, and he issued orders that under no circumstances was it to be withdrawn. When Gen. Patton soon learned that there was no bridgehead, he erroneously assumed that there had been a bridgehead that had been withdrawn in violation of his order, and he ordered the relief of command of CCB/7AD Commanding Officer Gen. Thompson as being the person responsible for failing to follow Patton's order -- which was corrected after the War but which had tragic consequences at the time.

The reason that Col. Yuill was overruled and ordered to make the crossing at Dornot was almost certainly due to the erroneous report that a successful crossing by the 23 AIB patrol had been achieved when in fact the patrol had been almost all killed and never reached the east bank. Col. Yuill was correct but was overruled, a mistake that cost great numbers of casualties in a failed effort that could have been far more successful with far fewer casualties if the commander on the ground had not been overruled.

-- Wesley Johnston

|

[7 Sep 1944] "Nevertheless, the order to cross at Dornot was sustained, and Colonel Yuill told his 2d Battalion to make the crossing before daylight, 8 September. Not long before, the 2d Battalion had detrucked at Buxieres; during late afternoon its Company E had been committed to clean out enemy road blocks in Gorze. Now the battalion was moving slowly on foot toward Dornot. Its troops, if they attacked before daylight, would have to do so without daylight reconnaissance and with maps of no larger scale than 1:100,000." (page 9)

The Terrain and the Forts

Pages 12-13

Dornot, the village that was to be the base for the projected assault crossing of the Moselle, was picturesquely situated on the sharply sloping sides of steep westbank hills. Its main road led into the town from the west and down a narrow main street to a junction with a northsouth highway running generally parallel to the river. Beyond the crest of the west-bank hills, the Dornot road and all of the town itself were under direct observation from dominant east-bank hills which began to rise a few hundred yards beyond the river. Atop two of the peaks of the first range of east-bank hills opposite Dornot perched Fort St. Blaise and Fort Sommy, known as the Verdun Group, embedded and camouflaged so as to be nearly invisible from the west bank. Although the forts were shown on the small-scale maps with which the assault troops were forced to work, hardly anything was known of their size or complexity.

In this section of the Moselle Valley a broad flood plain that stretched south from Metz began to narrow, but east of the river there was still a stretch of approximately 400 yards of flatland almost devoid of cover before the ascent to the hills began. Along it ran the broad Metz-Pont-à-Mousson highway, passing through Jouy-aux-Arches, a village one mile to the north whose name derived from ancient Roman aqueducts still in existence, and Corny, a village one mile to the south of the projected crossing site. The flat stretch of flood land on the west bank was smaller, only about 200 yards wide between the west-bank highway and the river. Here some cover was provided by a railroad embankment which ran generally parallel to the highway and the river. Slightly to the northeast of Dornot, between the railroad and the river, were a small lagoon and across from it on the east bank a small irregular-shaped patch of woods on flat ground between the river and the Metz highway. On the west bank, approximately onehalf mile north of Dornot stood the cluster of houses known as le Chine, which had been cleared the day before by the 23d Armored Infantry Battalion. Just north of le Chine lay the village of Ancy-sur-Moselle. Approximately one and one-half miles south of Dornot on the west bank and southwest of Corny was the larger village of Novéant.

Besides the two forts of St. Blaise and Sommy, the elaborate west-bank fortification, Fort Driant, with a connecting southern reinforcement, the Moselle Battery, provided the strongest opposition to a crossing of the Moselle in this sector. Built by the Germans between the wars of 1870 and 1914, Fort Driant had been designed primarily to defend the southwestern approaches to Metz, but it was sited so that its batteries dominated the Moselle Valley as well. Emplaced on the highest west-bank terrain feature in the vicinity, Fort Driant had already illustrated the effect of its batteries to the attacking American troops. Just north of Fort Driant across the Ars-sur-Moselle-Gravelotte defile stood another fortification, Fort Marival, whose guns could fire on the Dornot area. Farther to the north and almost due east of Gravelotte was the formidable Fort Jeanne d'Arc, from which fire might also reach the Dornot vicinity.

Accordingly, the urgency of exploiting German disorganization and reaching the Sarre River in effect impelled the Americans to attempt a crossing of the Moselle against great odds. Colonel Yuill and his men were aware that Forts St. Blaise and Sommy existed, but knew little of their capabilities. They were completely in the dark about the very existence of Forts Driant, Marival, and Jeanne d'Arc, for these German defenses did not even appear on the smallscale maps in the hands of the 11th Infantry. The regiment assumed that the fire that had actually come from the batteries of Fort Driant was the work of roving German guns. In addition, any crossing of the Moselle in the Dornot area at this particular time might possibly be subjected to enemy ground action on the near bank, for on the night of 7 September the situation around Novéant to the south and Ancy-sur-Moselle to the north was still fluid.

|

|

|

MacDonald: Preparation for the Crossing (8 Sep 1944)

[8 Sep 1944] "As morning approached on 8 September, troops of the 5th Infantry and 7th Armored Divisions were deployed as follows: To the north, outside the Dornot sector, CCA was digging in alongside the Moselle near Talange, northwest of Metz, and the 2d Infantry was facing a strong defense between Amanvillers and Verneville, abreast and west of Metz. The 10th Infantry was in 5th Division reserve and CCR in [XX] corps reserve. To the south, Force II (less Company B, 23d Armored Infantry Battalion) of CCB was in an assembly area north of Onville, and two companies of the 1st Battalion, 11th Infantry, were astride the high ground north and south of Arnaville. In the vicinity of le Chine and Dornot was Force I of CCB: the 23d Armored Infantry Battalion (including Company B); Company A, 31st Tank Battalion; and Company B, 33d Armored Engineer Battalion. (Force I's 2d Platoon, 814th Tank Destroyer Battalion, had previously been committed and virtually annihilated east of Rezonville, and the 434th Armored Field Artillery Battalion, while supporting Force I, was in firing positions just northwest of Rezonville.) Astride the high ground west and south of Dornot, ready to assist the crossing by fire, was the 3d Battalion, 11th Infantry, and in Dornot itself, the 2d Battalion, 11th Infantry. In the rear of Dornot was the remainder of the 11th Combat Team: the 11th Infantry (less its three rifle battalions); the 19th Field Artillery Battalion; Company C, 818th Tank Destroyer Battalion; Company C, 735th Tank Battalion; Company C, 5th Medical Battalion; Company C, 7th Engineer Combat Battalion; and an attached reconnaissance platoon of the 818th Tank Destroyer Battalion." (page 13)

[8 Sep 1944] "The mixture of CCB and 11th Infantry units had produced a maze of perplexity in the command picture. Both CCB and the 11th Infantry had orders to cross the Moselle at Dornot. General Irwin, 5th Division commander, had been given verbal orders by XX Corps placing him in command of all troops in the Dornot area; but this information had not reached General Thompson, CCB commander, and he thought he was in command." (pages 13-14)

[8 Sep 1944] "The men of Colonel Lemmon's 2d Battalion, 11th Infantry, were already having difficulty getting into Dornot, for vehicles of CCB had clogged the narrow road into the town. Further complicating the situation, rain began to fall, making the road even more treacherous in the darkness. Fire from Germans still on the west bank harassed traffic from the flanks, and when attempts were made to pull the armored vehicles out of the area the two-way movement only resulted in traffic jams at Gorze and Dornot." (page 14)

[8 Sep 1944] "It was still dark when rumor spread that a staff officer from XX Corps had appeared and ordered the [23rd] armored infantry to cross in advance of the 2d Battalion. Although this staff officer was never identified and his intervention denied by XX Corps, the idea, at least, was prevalent and added to the confusion.

[FOOTNOTE 16:] Moselle River Crossing; Ltrs, Gen Thompson to Hist Div; Intervs, Thompson, Morse, Coghill, Yuill, Lemmon, and Lemmon-Yuill; Ltr, Gen Walker to Hist Div, 6 Jan 49. Colonel Lemmon says that this staff officer definitely appeared at his command post in Dornot and gave such an order to him and to Colonel Allison, 23d Armored Infantry Battalion. In General Walker's letter, he says that he ordered an investigation later to determine the identity of this officer, but the investigation proved inconclusive.

" (page 14)

[8 Sep 1944] "Faced with the confusion on the ground and the probability that his men could not be ready for a crossing during darkness, Colonel Lemmon finally established

communications with his [11th] regimental commander, Colonel Yuill. Shortly after daylight, 8 September, Colonel Yuill told his 2d Battalion commander that he should proceed with his crossing plans and that the 23d Armored Infantry Battalion was attached for the crossing. The basis for such a statement was probably the verbal order given General Irwin earlier by XX Corps, that the 5th Division was to force a crossing and use the 23d Armored Infantry Battalion to augment its own infantry.

" (page 14)

[8 Sep 1944] "But a short while later General Thompson, CCB commander, used the communications of the 2d Battalion, 11th Infantry, [see FOOTNOTE 17] to telephone Colonel Yuill. Informing him of his mission to cross the Moselle, General Thompson requested permission to use a battalion of the 11th Infantry to assist his own 23d Armored Infantry, because his battalion had been seriously depleted in the battles to hold at Dornot and le Chêne. Since the general's mission was the same, since co-ordination was apparently the only solution to a confused situation, and since General Thompson was the senior officer on the ground, Colonel Yuill approved and designated Colonel Lemmon's 2d Battalion. This was a major step toward co-ordination, but there was nothing to indicate that General Irwin was aware of the negotiations, and there was no real co-ordination among supporting elements of the two divisions. Colonel Yuill, although having granted General Thompson's request, did not consider that his 2d Battalion was in any sense attached to CCB, only that General Thompson was in over-all command.

[FOOTNOTE 17:] General Thompson says 3d Battalion, but Colonel Lemmon and Colonel Yuill, recalling the incident in detail, say 2d Battalion.

[FOOTNOTE 18:] Intervs with Thompson, Lemmon, Yuill, Lemmon-Yuill; Ltr, Col Birdsong to Hist Div.

" (pages 14, 16)

[8 Sep 1944] "After his telephone conversation with Colonel Yuill, General Thompson made contact with the 7th Armored Division artillery officer. Since he had received no response to urgent messages of the day before to [7AD] division headquarters requesting assault boats, General Thompson told his artillery officer to avoid both division and corps headquarters but to secure as much artillery as possible for support of the crossing. He wanted a preparatory barrage of smoke and high explosive on the east-bank hills beyond Dornot for forty-five minutes prior to the assault. The 2d Battalion, 11th Infantry, meanwhile was making its own preparations for artillery support from its own [5th Infantry] division.

[FOOTNOTE 19:] Intervs with Thompson and Lemmon.

" (page 16)

[8 Sep 1944] "Although it would seem that two divergent efforts to cross the Moselle were being made at the same spot, real coordination finally came on battalion level and all preparations eventually worked toward one end. According to Colonel Lemmon, both he and the 23d Armored Infantry commander, Colonel Allison, recognized that the 2d Battalion, 11th Infantry, was the major unit and was giving the orders. The 2d Battalion's original plans had been made with the idea that elements of CCB would cross one thousand yards north of Dornot and take Jouy-aux-Arches, the latter town to be on the north flank of the 11th Infantry bridgehead. Now the two infantry battalion commanders decided that both units would cross near the small lagoon on the west bank, across from the irregular-shaped patch of woods on the east bank. The 23d Armored Infantry was to swing north, capture Luzerailles Farm, approximately halfway between Fort St. Blaise and Jouy-aux-Arches, and establish a defense in the southern edge of Jouy-aux-Arches, both positions to protect the north flank of the bridgehead. The 2d Battalion, 11th Infantry, was to advance immediately on Fort St. Blaise. The 3d Battalion, 11th Infantry, which would cross later, was to capture Fort Sommy and protect the south flank of the bridgehead.

[FOOTNOTE 20:] Intervs with Lemmon and Lemmon-Yuill.

" (page 16)

[8 Sep 1944] "Because supporting artillery was not completely in firing position, General Thompson and Colonel Yuill, apparently at about the same time and with approval of the 5th Division commander, decided to postpone the attack. Another factor in delay was the lack of assault boats. Only those few brought to Dornot by the 11th Infantry's attached platoon of Company C, 7th Engineer Combat Battalion, were present until about 0800 when some twenty additional boats arrived. The arrival of these boats was the result of a lengthy trip during the night through rear areas by General Thompson himself, after his repeated requests for boats the day before had brought no results.

[FOOTNOTE 21:] Intervs with Lemmon, Lemmon-Yuill, Yuill, Thompson, Morse, Coghill; Ltrs, Gen Thompson to Hist Div.

" (pages 16-17)

[8 Sep 1944] "Plans for the crossing proceeded, some apparently made by General Thompson, others by the two battalion commanders, and some by Colonel Yuill, 11th Infantry commander. The main fact was that the 2d Battalion, 11th Infantry, would furnish the bulk of the troops, for in the battles at le Chine and Dornot the 23d Armored Infantry had been reduced to about half its normal strength and was depleted even further when Company A was ordered to hold the left flank of the near bank at le Chene. The 3d Battalion, 11th Infantry, from its positions atop the high ground south of Dornot, was to assist the crossing with machine gun and mortar fire, while its Company L sent a platoon to investigate Novéant and place outposts in the town as south-flank protection for the crossing. This Company L platoon subsequently found Novéant unoccupied but withdrew in the afternoon when plans were made for a 3d Battalion crossing. Two companies of the 1st Battalion, 11th Infantry, were still in position astride the high ground around Arnaville, with elements of Company B assigned to clear the enemy from a pocket at Ste. Catherine's Farm, between Gorze and Dornot.

" (page 17)

[8 Sep 1944] "With the confusion of men and vehicles still existing in the Dornot vicinity, at 0930 General Thompson ordered the vehicles of his combat command [CCB/7AD], including the 31st Tank Battalion, which was close behind Dornot, to move from the area. Remaining were CCB's armored infantry, engineers, and medics. Apparently not all vehicles succeeded in clearing the area, for the infantry complained that a number of armored cars with their bright cerise air-identification panels were left parked in the open along the road leading from Dornot to the river, drawing enemy artillery fire. The confusion between 7th Armored and 5th Division troops was finally dissipated on 9 September when CCB was officially attached to the 5th Division in exchange for attachment of the 2d Infantry Regimental Combat Team to the 7th Armored Division.

[FOOTNOTE 22:] Eleventh Infantry; Intervs with Thompson, Morse, Lemmon-Yuill.

" (page 17)

|

|

MacDonald: The Assault Begins (8 Sep 1944)

[8 Sep 1944] "Ready to support the crossing on the morning of 8 September were the 19th, 21st, 46th, and attached 284th Field Artillery Battalions of the 5th Division and the 434th Armored and attached 558th Field Artillery Battalions of the 7th Armored Division. The new hour of assault was set for 1045. Under cover of heavy blanket concentrations by the artillery (few point targets could be discerned) and a smoke screen on Forts St. Blaise and Sommy, the infantry, assisted by the platoon of Company C, 7th Engineers, and elements of Company B, 33d Armored Engineers, moved the assault craft to the water's edge. Using an underpass beneath the railroad track, they moved northeast to a spot between the lagoon and the river across from the small irregular-shaped patch of woods on the east bank. (To the troops in the action, this woods became known, apparently because of a horseshoe-shaped defense later set up there, as the "horseshoe woods.") Enemy shelling and machine gun fire began to harass the infantrymen from the moment they moved through the railroad underpass. At least one infantry squad carrying an assault boat received a direct hit. It became necessary to call for more supporting artillery fire and to send a patrol from the 23d Armored Infantry Battalion to the north to eliminate enemy small arms fire. This patrol finally knocked out the west-bank opposition and captured some twenty prisoners.

" (pages 17, 20)

[Wesley Johnston Note: 558th Field Artillery Battalion was attached to but not organic to 7th Armored Division.]

|

[8 Sep 1944] "Not until about 1115 did Company F, led by its company commander, 1st Lt. Nathan F. Drake, in the lead boat, launch the assault in five assault craft. The crossing was contested by rifle and machine gun fire from the east bank and mortar and artillery fire that wounded several Company F and engineer troops. Before loading in assault boats, each wave of infantry would take cover in a shallow ditch about twenty yards from the river, then make a dash through the enemy fire to reach the boats. Next to cross, despite continued enemy fire which killed one man and wounded five, was Company G. By 1320 all of Companies F and G, plus a platoon of heavy machine guns and 81-mm. mortars from Company H, were across the river, and Company E had begun its crossing. Once beyond the river, the men fanned out in the woods for local security and began to reorganize. The elements of Companies B and C, 23d Armored Infantry, whose combined strength now totaled only forty-eight men, including Colonel Allison, the battalion commander, and his forward command group, went across intermingled with the two lead companies [F and G] of the 2d Battalion, 11th Infantry.

[FOOTNOTE 23:] Moselle River Crossing; Eleventh Infantry; Fifth Infantry Division; 11th Inf S-3 Jnl, 8 Sep 44; Ltr, Capt Morris M. Hochberg (commander of the [33rd] armored engineers) to Hist Div, 21 Apr 50; Intervs with Thompson, Lemmon, Lemmon-Yuill; Ltrs, Gen Thompson to Hist Div. The 2d Battalion, 11th Infantry, Unit Journal, is of little value since entries for this period were later destroyed by enemy artillery fire. See also AAR's of 23d Armd Inf Bn and CCB, 7th Armd Div, and arty units, Sep 44.

" (page 20)

|

[8 Sep 1944] "Valuable fire support in the Dornot crossing was furnished by the machine guns, mortars, and 57-mm. antitank guns of the 3d Battalion, 11th Infantry, from positions on the bluffs south of Dornot. Forward observers attached to the 3d Battalion from the 19th Field Artillery Battalion made good use of the commanding observation to adjust fires in support of the 2d Battalion, 11th Infantry. Artillery liaison officers from both 5th Infantry and 7th Armored Division artillery were with Colonel Lemmon, 2d Battalion commander. The howitzers of Cannon Company, 11th Infantry, were in direct-fire positions on the heights just south of Dornot.

[FOOTNOTE 24:] Ltr, Col Birdsong to Hist Div; Intervs with Yuill and Lemmon

" (page 20)

|

[8 Sep 1944] "The engineer plan for the crossing had called for the 537th Light Ponton Company (1103d Engineer Combat Group), assisted by one platoon of Company C, 160th Engineer Combat Battalion, to construct and operate infantry support rafts. Company C, 150th Engineer Combat Battalion, Company B, 160th Engineers, and elements of the 989th Treadway Bridge Company were to construct a treadway bridge in the vicinity of Dornot. But continued enemy machine gun, mortar, and artillery fire forced abandonment of this plan on the first day. The corps engineers were held back by Colonel Yuill, 11th Infantry commander, who realized that bridgebuilding under the circumstances was impossible. Except for two platoons the corps engineers either remained in their assembly areas or did mine clearance on rear-area roads. One of these platoons, the 1st Platoon, Company C, 150th Engineers, moved to the crossing site in early afternoon on reconnaissance but met intense enemy fire. Instead of preparing for bridge construction, the platoon was pressed into service assisting the ferrying of troops and supplies and evacuating wounded. When this platoon was relieved after dark by the company's 2d Platoon, the platoon of 7th Engineers and elements of Company B, 33d Armored Engineers [7th Armored Division], were also relieved. Ferrying operations thus passed to control of the 2d Platoon, Company C, 150th Engineers. During the afternoon one squad of the [33rd] armored Engineers had cut the railroad tracks in preparation for building a road over the tracks to the river.

[FOOTNOTE 25:] 1103d Engr (C) Gp and 150th Engr (C) Bn AAR's, Sep 44; Interv with Yuill; Ltr, 1st Lt Kingsley E. Owen (formerly Ex Off, Co B, 33d Armd Engr Bn) to Hist Div, 21 Apr 50.

" (pages 20-21)

[8 Sep 1944] "According to the original plan for the assault crossing the 3d Battalion, 11th Infantry, was to await the initial success of the 2d Battalion's effort and then cross the river farther to the south. Reconnaissance by the battalion S-3 and an attached engineer officer revealed a likely site in the northern outskirts of Novéant. Although the battalion commander issued tentative orders for the attack, it was delayed to await the outcome of the 2d Battalion's attempts to expand the bridgehead opposite Dornot. Subsequent action at the 2d Battalion site caused cancellation of plans for a second crossing, and at 1705 Company K was ordered to cross at Dornot, to be followed as soon as possible by the remainder of the 3d Battalion. Approximately one and one-half platoons of Company K had reached the east bank by 1745, despite being held up by heavy enemy mortar fire and confusion with the rear elements of Company E, which was receiving machine gun fire from its left front and still blocked the crossing site. The remainder of Company K managed to cross at intervals during early evening, but the confined situation in the bridgehead forced cancellation, for the moment at least, of plans to send over the rest of the 3d Battalion.

[FOOTNOTE 26:] 3d Bn, 11th Inf, Unit Jnl, 8 Sep 44; Eleventh Infantry.

" (page 21)

|

[8 Sep 1944] "Not all the second company [apparently a reference to G/11/5ID] had crossed when shortly after noon General Thompson, CCB commander, received a message to report to 7th Armored Division headquarters. Here he was relieved of command of CCB and subsequently reduced in rank. One of the reasons given for his relief was that CCB had established a bridgehead across the Moselle on 7 September and then had withdrawn it contrary to the orders of the XX Corps commander [Gen. Walton Walker]. This was not a fact, for no bridgehead had been established on 7 September: this was only the small patrol which had crossed in three boats and had been almost annihilated. General Thompson was later exonerated and restored to the rank of brigadier general. (27)

The departure of the CCB commander, the only officer above the rank of lieutenant colonel present thus far in the vicinity of the crossing site, placed full responsibility for the river crossing in the hands of the 11th Infantry. From this time on there was apparently no question but that it was an 11th Infantry bridgehead supported by the 23d Armored Infantry Battalion of CCB. (28)

[FOOTNOTE 27:] Interv with Thompson. See also in the OCMH files a copy of the letter sent to the Chief of Staff by General Thompson, 6 October 1944, explaining the points raised in the letter which initiated his relief. General Thompson was advanced to brigadier general by Special Orders 210, 20 October 1948, under provisions of Section 203 (a) of the Act of Congress, approved 29 June 1948 (PL 810 80th Cong).

[FOOTNOTE 28:] Intervs with Yuill and Lemmon-Yuill.

" (pages 21-22)

|

|

MacDonald: The German Reaction (8 Sep 1944)

[8 Sep 1944] "From the German viewpoint the crossing of the Moselle was almost as confused as the original American preparations. Defending the east bank at the time of the assault were the 282d Infantry Battalion ("Battalion Voss"), made up of men with stomach ailments, and the SS Signal School Metz (''Battalion Berg"), both under the command of Division Number 462. Headquarters for Battalion Berg was in Jouy-aux-Arches; for Battalion Voss in Corny. The Americans had crossed the river on the boundary between the two battalions, a line through the middle of the horseshoe woods.

" (page 22)

[8 Sep 1944] "The only other German troops in the vicinity of the crossing site were the 37th SS Panzer Grenadier Regiment of the 77th SS Panzer Grenadier Division. This regiment had arrived east of Metz on 6 September after a road march of approximately fifty miles from the vicinity of Saarlautern. On 7 September the regiment's 2d Battalion (battle strength: 620 men) had been ordered to Marly, some three miles east of Jouy-aux-Arches. Attached to the 2d Battalion was a company of armored infantry, seven Flak tanks, (29) two assault guns and one 75-mm. self-propelled gun. Having arrived in Marly in midafternoon (7 September), the battalion during the evening passed to control of Division Number 462.

[FOOTNOTE 29:] The Flak tank (Flakpanzer) is a hybrid armored vehicle consisting of a light or medium antiaircraft gun mounted on a tank chassis.

" (page 22)

[8 Sep 1944] "About 1000, 8 September, the date of the American crossing, the bulk of the 2d Battalion, 37th SS Panzer Grenadier Regiment, moved to Augny, between Marly and Jouy-aux-Arches. At noon one of the company commanders reported that he had talked with a wounded man who said the Americans had crossed the river but were equipped with no weapons heavier than submachine guns. A little more than an hour later, when a message from the German corps headquarters indicated that about one company of Americans had crossed the river at the horseshoe woods, the commander of the 2d Battalion sent a patrol to Jouy-aux-Arches to determine the truth of the report. The patrol returned at 1430 with a written message from the commander of Battalion Berg stating that the enemy had crossed north of Corny, that a large part of Battalion Voss had been routed, and that there had also been some penetration in the sector of Battalion Berg (SS Signal School Metz). Although the enemy could be thrown back if reserves were brought up, the message stated, the SS Signal School had no reserves available, and "the situation is serious, unless reinforcements arrive."

" (page 22)

[8 Sep 1944] "Meanwhile, several reports had been received from Battalion Voss that there was "no change in [the] situation." Because this news contradicted his information from Battalion Berg, the 2d Battalion commander sent a noncommissioned officer to Corny to find out what actually was taking place. He returned with a message from the commander of Battalion Voss stating, somewhat explicably, that a company of the latter battalion "took off." Perhaps this news explained the earlier report that a large part of Battalion Voss had been routed, but it failed to indicate that there had been an American crossing. In the face of these contradictory messages, the 2d Battalion commander planned originally to commit only two reinforced platoons, one moving south from Jouy-aux-Arches and one moving north from Corny, with the mission of throwing back the enemy—if found. When continuing reports from Battalion Berg in Jouy-aux-Arches indicated that a bridgehead had been established and that reinforcements were crossing the river, he changed his plans. He ordered his 7th Company to move to Corny and attack north and his 5th Company to Jouy-aux-Arches and attack south. The 8th Company, a heavy weapons company, was to support the attacks with infantry howitzer and mortar fire. The companies moved out for the attack at 1515.

[FOOTNOTE 30:] For a detailed report of this action from the German side, see pages from the war diary of the 2d Bn, 37th SS Pz Gren Regt, found in a file of miscellaneous papers, labeled Allg., 1, 2, 3, 4/SS Pz. Gren. Rgt. 37 (Feldgericht) (hereafter cited as 37th SS Pz. Gren Regt Miscellaneous File). This file contains an odd collection of documents, most of them records of disciplinary actions taken by the 1st Bn of the regiment. The 282d Inf Bn has been identified through 5th Div G-2 sources only.

" (pages 22-23)

|

|

MacDonald: Advance to Fort St. Blaise (8 Sep 1944)

[8 Sep 1944] "At the horseshoe woods, while the early effort of the 3d Battalion, 11th Infantry, to reinforce the bridgehead had been taking place, Companies F and G had, in late afternoon of 8 September, moved out of the woods in an advance across the Metz highway and up the slopes leading to Fort St. Blaise, more than 2,000 yards beyond the river. (Map 1) Company E, still reorganizing in the woods, was to follow when reorganization was complete and mop up bypassed resistance. Company K, when other elements of the 3d Battalion were able to cross, was to capture Fort Sommy. Although the 23d Armored Infantry Battalion had been ordered to take Luzerailles Farm and the southern edge of Jouy-aux-Arches, the small number of armored infantry to cross apparently negated this original plan, for no attempt was made to execute it.

" (page 23)

MAP 1 - Click on image for full size.

[8 Sep 1944] "Accompanied by Capt. Ferris Church, the 2d Battalion S-3, the two lead companies moved out, Company F forward and Company G echeloned to the left rear. Climbing the steep slope past occasional patches of trees and through vineyards and irregularly spaced fruit trees, the men met virtually no enemy opposition and only a strange silence from the fortification at the top of the hill. There were no casualties in the advance until Company F had reached the outer defenses of Fort St. Blaise. There the company commander, [1st] Lieutenant [Nathan E.] Drake, leaned over a wounded German to ask him a question. As the lieutenant straightened and raised his head, one of three German riflemen hidden scarcely ten yards away shot him through the forehead. He died instantly as the men about him turned their weapons on the three Germans. Command of the company fell to 1st Lt. Robert L. Robertson.

[FOOTNOTE 31:] Unless otherwise noted, this section is based on the following: Moselle River Crossing; Combat Interv 38 with Sgt Hugh B. Sikes and Cpl Otto Halverson, 3d Plat, Co G, 11th Inf (hereafter cited as Combat Interv 38 with Sikes, Halverson); Eleventh Infantry; Fifth Infantry Division; Intervs with Lemmon and Lemmon-Yuill.

" (page 23)

[8 Sep 1944] "Continuing its advance, Company F slowly and methodically cut its way through five separate double-apron barbed wire obstacles, only to come up against an iron portcullis studded with curved iron hooks that prevented scaling. On the other side of the portcullis a dry moat about thirty feet wide and fifteen feet deep surrounded the fort. The fort itself was a huge domed structure of three large casemates constructed of concrete and covered by grassy earth which provided excellent camouflage and additional protection. Although the men of the 2d Battalion did not know it, Fort St. Blaise was manned at this time by only a weak security detachment of a replacement battalion which withdrew as the Americans approached.32

[FOOTNOTE 32:] MS # B-042 (Krause). Colonel Lemmon says, "Undefended or not, our people got fire from the fort and heard Germans inside." See Interv with Lemmon-Yuill.

" (pages 23-24)

[8 Sep 1944] "Not knowing that the fort was undefended, Captain Church, after radio consultation with his battalion headquarters [2nd Bn, 11th Inf Rgt], ordered his two companies [F and G] to pull back about 400 yards to permit the artillery to plaster the fort before the final assault. The companies did pull back but, when the supporting artillery fired, three rounds fell short, wounding several of the Americans and killing three. The American artillery fire seemed a cue for a heavy concentration of German mortar and artillery fire, and at the same time (about 1730) German infantry began counterattacking on both flanks and infiltrating in the unprotected rear of the two companies. Over his radio Captain Church ordered Company E to move up quickly to close the gap between it and the advance elements. But it was too late. Intense machine gun cross fire swept in from both flanks, and the broad Metz highway and the flatland on either side of it had become a deathtrap.

[FOOTNOTE 33:] Moselle River Crossing; Combat Interv 38 with Sikes, Halverson. Because no mention of short rounds is made in artillery journals, it seems possible that these "short rounds" were from German artillery at Fort Driant or from one of the other west-bank forts. According to an interview with Colonel Lemmon there were more than three rounds. From his observation post in Dornot, he could see a battalion volley land among his troops. Checks through his 5th Division and 7th Armored Division artillery liaison officers revealed, he says, that the fire was from a 7th Armored Division artillery unit and had been called for by the 7th Armored Division artillery liaison officer in his headquarters. The artillery liaison officer had the fire lifted immediately.

" (page 25)

[8 Sep 1944] "The enemy threatened at any moment to split the battalion. Captain Church's forward companies [F and G/11th Inf Rgt] were stretched out so precariously on the open slope of the hill that he ordered a withdrawal back to the woods. So effective was the enemy infiltration in the battalion rear by this time that the withdrawal was planned as an attack downhill in a skirmish line. But vineyards and patches of woods and enemy fire prevented control of the skirmish formation, and the two companies separated, each coming down the hill in a ragged single column. An old German trick of firing one machine gun high with tracer bullets and another lower to the ground with regular ammunition took its toll. The retreat moved slowly and casualties were heavy. As darkness approached and visibility decreased, unit commanders told their men to make a last dash for the woods; if a man was hit, he was to be left alone to crawl the rest of the way as best he could. The bulk of the companies were three hours in returning to the horseshoe woods, and some men were still straggling in at daylight the next morning. The dead and wounded marked the path of withdrawal. Although medics went out during the night and the next day to care for the wounded, they were often shot down at their tasks.

" (page 25)

[Wesley Johnston Note:] At this time (18 Apr 2022), the only 8 Sep 1944 death I know of for F/11IR is Lt. Drake. All other 8 Sep deaths were in Company G or Company E. Companies F and G were the ones coming down the slope. Company E had been sent in to try to close with F and G when the German flank attack threatened to cut off F and G. I do not have the MOS for these men so that I do not know which were medics.

[8 Sep 1944] "Earlier in the afternoon of 8 September, after the German commander of the 2d Battalion, 37th SS Panzer Grenadier Regiment, located at Augny, had ordered a counterattack by two of his companies, the 5th Company had reached Jouy-aux-Arches at 1700 and the 7th Company had reached Corny at 1715. Although the 5th Company soon launched its attack to the south, the 7th Company in Corny was immediately pinned down by strong American artillery and machine gun fire from west of the Moselle and suffered heavy losses. Because of another message from Battalion Berg in Jouy-aux-Arches at 1620, indicating that the town could not be held unless reinforcements arrived (the 5th Company had not yet reached Jouy), the commander of the 2d Battalion decided to commit his 6th Company to attack "objective: Jouy-aux-Arches." By 1800 the 6th Company had reached the town, no doubt finding it still in German hands. The 5th Company reported one minute later that it had reached the horseshoe woods and had taken twenty-five prisoners. The 7th Company was still pinned down at Corny.

" (pages 25-26)

[8 Sep 1944] "But now the 2d Battalion commander received a message indicating that the Americans had occupied Fort St. Blaise. At approximately the same time, the commander of Division Number 462 reached the 2d Battalion's command post in Augny and stressed the importance of retaking the fort. Accordingly, the 6th Company in Jouy-aux-Arches was committed to "retake" Fort St. Blaise. Under "heaviest [American] artillery fire," the 6th Company attacked and occupied the fort at approximately 2200 without making contact with the Americans or suffering any casualties. The Germans believed that the Americans had had to evacuate the fort because of their own artillery fire.

" (page 26)

[8 Sep 1944] "Meanwhile, in Augny, two companies of the 208th Replacement and Training Battalion had arrived and were sent to Jouy-aux-Arches to reinforce Battalion Berg. About 2100, German reserves had been further increased when a Luftwaffe signal battalion and the 1st Battalion, 37th SS Panzer Grenadier Regiment, had arrived in Augny.

[FOOTNOTE 34:] 37th SS Pz Gren Regt Miscellaneous File.

" (page 26)

[8 Sep 1944] "Upon withdrawal of the two American assault companies [F and G/11IR], the men of the 23d Armored Infantry Battalion [7th Armored Division] and Companies E and K, 11th Infantry, began to dig in along the perimeter of the horseshoe woods. As troops of Companies F and G straggled into the original bridgehead area, 2d Lt. John A. Diersing, commanding Company E after its original commander had been wounded, his 1st sergeant, Claud W. Hembree, and other officers and noncommissioned officers directed the survivors into defensive positions. All that the day's efforts and high casualties had gained was a minuscule bridgehead 200 yards deep and 200 yards wide, encompassing no more than the horseshoe woods. Only heavy concentrations from the supporting artillery battalions prevented the Germans from retaking even this small gain and protected the Americans as they dug in. The men were still digging in when the first "counterattack" against the bridgehead itself began: three enemy tanks drove along the highway from the north, spraying the woods line with bullets and shell fragments. Although protected by "bazooka pants," the tanks would not close with the defenders, their crews contenting themselves with trying to draw fire to determine the exact location of the American positions. The defenders' line was hard hit, particularly the positions of Company E at the point of the horseshoe, but the men held their fire. A group of enemy infantry, estimated at company size, heavily armed with automatic weapons, and shouting loudly, "Yanks kaput!" followed soon after the tanks. This time Company E opened fire, but the enemy infantry did not close, continuing to follow their tanks until out of sight to the right.

" (page 26)

[8-9 Sep 1944] "Almost hourly for the remainder of the night (8-9 September) the Germans counterattacked, mainly with rifles and burp guns. As the enemy formed across the highway, the defenders could hear shouted orders, followed by almost fanatical charges with the enemy bunched and yelling. The American automatic rifles had a field day, and turned back every attack with high casualties for the Germans; but the defenders were only partially dug in, if at all, and casualties among the Americans were also numerous. The woods were filled with cries for medics. Sergeant Hembree, Company E, realizing that such calls would disclose positions, as well as indicate the number of casualties, and that all available aid men were working near the river in an improvised aid station, sent around an order that no one was to cry out. The exhibition of self-discipline that followed was one of the heartening feats of courage during the hectic days in the bridgehead.

" (pages 26-27)

[8-9 Sep 1944] "During the first-night counterattacks, two men of Company K, Pfc. George T. Dickey and Pfc. Frank Lalopa, who had volunteered to man an outpost beyond the main line of resistance, stuck to their post despite a warning order to withdraw. Armed only with M-1 rifles, the two men held off the enemy until finally they were surrounded and killed. The next morning when other men of Company K crawled out to the position, they found the bodies of twenty-two Germans, some within three yards of the bodies of Dickey and Lalopa.

" (page 27)

[8 Sep 1944] "Soon after the defense was organized, Captain Church returned to the battalion command post [2nd Bn/11IR] on the west bank to report the situation. Left in command of the bridgehead forces was the Company G commander, Capt. Jack S. Gerrie. While the battalion commander, Colonel Lemmon, had realized that the situation east of the river was serious, he was further impressed by Captain Church's report and requested permission to evacuate his battalion. Colonel Yuill in turn asked permission of division [5ID]. Although General Irwin was aware that the situation in the bridgehead was far from satisfactory, XX Corps refused to permit withdrawal until another bridgehead was secured. A crossing by elements of the 80th Division of XII Corps to the south had been beaten back, and the precarious foothold opposite Dornot was thus the only remaining bridgehead across the Moselle. If the Dornot crossing could be held while the 10th Infantry made another crossing farther south, General Irwin reasoned, there would be a chance to expand the Dornot bridgehead to link up with the 10th Infantry. He therefore denied Colonel Lemmon's request. The Dornot bridgehead was to be held "at all costs."

[FOOTNOTE 35:] Colonel Lemmon intended going into the bridgehead the first day, but when his advance command group went forward in midafternoon to establish a command post the men met intense enemy fire. From this time on, Colonel Lemmon felt that he could exercise better command and co-ordination from the west bank. His CP was in Dornot throughout the battle, although it had to be moved often because of enemy shelling. Interv with Lemmon.

[FOOTNOTE 36:] Gen Irwin, Personal Diary, loaned to Hist Div by Gen Irwin (hereafter cited as Irwin Diary), entry of 8 Sep 44; Interv with Yuill. (Quotation from Irwin Diary.)

" (page 27)

|

|

MacDonald: Support of the Dornot Bridgehead (8 Sep 1944)

[8 Sep 1944] "After its heavy preassault bombardment and until daylight of 9 September, supporting artillery, particularly the direct-support 19th Field Artillery Battalion under command of Lt. Col. Charles J. Payne, fired heavily in support of the 2d Battalion bridgehead. During the twenty-four-hour period the 19th Field Artillery Battalion fired 1,483 rounds. Most concentrations were on call by SCR-300 from the infantry in the bridgehead, giving support which the infantry deemed "excellent and plentiful." The work of the 19th Field Artillery Battalion's liaison officer, Capt. Eldon B. Colegrove, drew particular praise. He remained on duty on the west bank relaying requests for fire the entire time the 2d Battalion held on the east bank. Observers for the 5th Division artillery units were either in Dornot or on the bluffs overlooking the river and thus had good over-all observation on the bridgehead area. One observer from the 7th Armored Division was in the bridgehead itself.

" (pages 27-28)

[Wesley Johnston Note:] Per this account, the only artillery forward observer in the bridgehead was one FO from one of the 7th Armored Division artillery units. I have not yet identified who that was (as of 18 Apr 2022).

[8 Sep 1944] "During the afternoon of 8 September, further forward displacement of supporting artillery was accomplished. While the attached 284th Field Artillery Battalion maintained direct support, the 19th Field Artillery Battalion advanced to the vicinity of Ste. Catherine's Farm. One gun of Battery B, 46th Field Artillery Battalion, displaced to a position east of Gorze but, when subjected to what was believed to be observed enemy artillery fire, retired to new positions just west of Gorze. Here it was joined by the remainder of the battalion for a displacement in effective range of approximately

3,000 yards.

" (page 28)

[8 Sep 1944] "While armor had been available in the Dornot vicinity in early stages of the operation, it had been pulled out because of unsuitable terrain and lack of cover, and crossing armor into the tiny bridgehead was still impossible. Company C, 735th Tank Battalion, a part of the 11th Combat Team, remained uncommitted, but one platoon of Company C, 818th Tank Destroyer Battalion, took position during the day on the high ground southwest of Dornot and engaged targets east of the river.

[FOOTNOTE 37:] Moselle River Crossing; 19th FA Bn, 46th FA Bn, 735th Tk Bn, 818th TD Bn AAR's, Sep 44; Interv with Lemmon.

" (page 28)

[8 Sep 1944] "Although repeated requests for air support had filtered back through higher echelons all day, none was forthcoming. Priority assignment of air to the fight for the Brittany port of Brest and to "riding herd" on the Third Army's open southern flank prevented its employment.

[FOOTNOTE 38:] Irwin Diary; 5th Div G-3 Jnl, 8 Sep 44; Cole, The Lorraine Campaign, Ch. III, p. 143, citing Ninth AF Opns Jnl, 9 Sep 44; XIX Tactical Air Command, Operations File, 1 Sep-15 Sep 44, inclusive (hereafter cited as XIX TAC Opns File).

" (page 28)

[8 Sep 1944] "The commander of the 1103d Engineer Combat Group, Lt. Col. George H. Walker, still planned to build a bridge across the river opposite Dornot the night of 8-9 September, but again enemy fire proved too intense. Additional assault boats were brought up to increase the means of supply and evacuation of wounded and to replace boats that had been knocked out or sunk. The 2d Platoon, Company C, 150th Engineers, continued to operate the assault boats until 1400, 9 September, when relieved by a platoon of Company C, 204th Engineer Combat Battalion. Orders had been received late on 8 September detaching the 150th Engineers and assigning the battalion to duty with the XII Corps to the south.

[FOOTNOTE 39:] 1103d Engr (C) Gp, 150th Engr (C) Bn, 204th Engr (C) Bn AAR's Sep 44.

" (page 28)

[8 Sep 1944] "When crossing the Moselle on 8 September, each man of the 2d Battalion and Company K, 11th Infantry, had taken with him all the ammunition he could carry and the usual canteen of water, but no rations. Beginning at 2200 that night, ten men of the 2d Battalion Reconnaissance Platoon carried all types of infantry ammunition, three units of K ration per man within the bridgehead, and 250 gallons of water to the crossing site. The engineers subsequently loaded the supplies and pulled the boats across the river with ropes. Two crossings per boat were made without mishap until the last boat on its second trip was hit near the far shore by an enemy shell and five men were killed.

" (pages 28-29)

[8 Sep 1944] "The 2d Battalion medical aid station, set up in Dornot early on 8 September, merged during the afternoon with that of the 3d Battalion, 11th Infantry, which had moved into two cellars across the street. Although litter squads were attached initially to the rifle companies, only one squad managed to get across the Moselle, and the others worked on the near shore. Litter bearers first transported patients to the railroad underpass; from there a jeep ran the gantlet of shellfire into Dornot. The exposed nature of the road across the western hills from Dornot still necessitated a jeep carry from the aid station to an ambulance loading point behind the hills. Later in the afternoon enemy small arms fire raking the open ground between the railroad and the river prevented movement even of litter teams until after dark. During this period 2d Lt. T. H. Pritchett, medical administrative officer of the 3d Battalion, and T/5 Charles R. Gearhart, liaison agent from Collecting Company C, 5th Medical Battalion, crawled into this fireswept area, gave first aid to three wounded men, and crawled out again, pulling the patients behind them. After dark, when sleet began to fall, further adding to the discomforts of the wounded, 2d Lt. Edwin R. Pyle, 2d Battalion medical administrative officer, crossed into the bridgehead and supervised removal of wounded by boat to the west bank, where the litter-jeep relay used earlier transported the patients to Dornot. After Lieutenant Pyle returned to the west bank about 0430, 9 September, evacuation was accomplished solely by infantrymen and aid men within the bridgehead who somehow managed to find boats or expedient floats and moved their wounded comrades to the west bank.

[FOOTNOTE 40:] Moselle River Crossing; Combat Interv 38 with Sikes, Halverson; Eleventh Infantry.

" (pages 28-29)

[8 Sep 1944] "At 2200 the night of 8 September the 10th Infantry received orders to cross the Moselle on 10 September in the vicinity of Arnaville, south of Novéant. A second bridgehead was to be attempted, this time allowing a reasonable period for planning and co-ordination. In the meantime, the battle to hold opposite Dornot went on.

[FOOTNOTE 41:] 10th Inf Unit Jnl, 8 Sep 44.

" (page 29)

|

|

MacDonald: Holding the Dornot Site, 9-10 September

[9 Sep 1944] "By the morning of 9 September expectation evidently still existed above regimental level that the 11th Infantry's bridgehead could be expanded and pushed to the south. Within the bridgehead itself there was no such optimism. The men inside the little perimeter knew that, if the German pressure continued as it had during the night, the foothold could not even be held for long. The regimental commander, Colonel Yuill, understood the situation and thus made no attempt to reinforce the bridgehead. Any such attempt, he knew, would be suicidal.

[FOOTNOTE 42:] Irwin Diary; 5th Div G-3 Jnl, 9 Sep 44.

[FOOTNOTE 43:] Interv with Yuill.

" (page 29)

[9 Sep 1944] "Before daylight on 9 September a report from a German prisoner that there were about one thousand Germans in one of the forts of the Verdun Group set off frantic requests for air support to hit the forts at daylight. Colonel Yuill, telephoning a number of times to 5th Division headquarters, said that "the bridgehead is desperate" and "it is vitally important that we get an air mission." The request was approved soon after daylight and planes were expected momentarily, but they did not arrive. At 0920 (9 September), General Irwin telephoned the XX Corps commander, General Walker, to protest the fact that the planes had been promised but had not appeared. While the 11th Infantry continued to cry frantically for planes, division promised that, if nothing else, "they would send cubs" (artillery observation planes). But at 1045 the regiment received the word it had apparently been fearing. The planes had been taken for missions against the primary target of Brest.

[FOOTNOTE 44:] 5th Div G-3 Jnl, 9 Sep 44.

" (pages 29-30)

[9 Sep 1944] "Enemy pressure against the little bridgehead continued. Counterattack followed counterattack: during the entire time the battalion remained on the east bank an estimated thirty-six separate enemy assaults were hurled against it.

[FOOTNOTE 45:] Although interviews and unit histories say "36 separate counterattacks," the morning reports of the units involved, particularly the valuable reports of Company K, 11th Infantry, would seem to indicate no such large number. While the enemy launched several determined counterattacks against the bridgehead, others were no doubt local assaults. What matters is that the enemy kept up continuous pressure. See Daily Rpts, 8-11 Sep 44, found in Heeresgruppe "G" Kriegstagebuch 2 (Army Group G War Diary 2), Anlagen (Annexes) 1.IX.-30.IX.44 (hereafter cited as Army Group G KTB 2, Anlagen 1.IX.-30.IX.44); 37th SS Pz Gren Regt Miscellaneous File.

" (page 30)

[9-10 Sep 1944] "Throughout the day of 9 September, and except for occasional lulls on 10 September, the rain of enemy shells continued, not only on the horseshoe woods and the crossing site but on Dornot, le Chine, the high ground on either side of Dornot, and the road to the west from Dornot. The Germans made the most of their commanding observation from Forts St. Blaise and Sommy, both of which proved impervious to American artillery fire; and the positions of the enemy's heavy guns and mortars could not be detected, not even from artillery observation planes. Shelling forced abandonment of all efforts to resupply the bridgehead in daylight, daytime activity resolving into hazardous efforts to evacuate the wounded. One of the wounded was Colonel Allison, the 23d Armored Infantry Battalion commander, [underlining added]the only field grade officer to cross into the bridgehead. Although evacuated, he died of wounds six days later.

" (page 30)

[9-10 Sep 1944] "Despite a tendency toward bunching and almost banzai-like attacks, the enemy facing the horseshoe defense was wily and, it seemed to the defenders, often fanatical. Sometimes his attacks were supported by tanks which would give close-in artillery and machine gun support while the accompanying infantry closed with persistence and courage.

" (page 30)

[9-10 Sep 1944] "After the first day's attack by elements of the 2d Battalion, 37th SS Panzer Grenadier Regiment, the next major German attempt to eliminate the bridgehead was launched at 2245 the night of 9 September by two companies of the 37th SS Panzer Grenadier Regiment, supported by fire from a third company of the same regiment. The attack marked the first mention in this action of this regiment's 4th Battalion. (The 1st Battalion had previously taken over defense of Forts Sommy and St. Blaise.) The attack proceeded satisfactorily until shortly after midnight when it bogged down under heavy American small arms fire. The Germans intimated that they had failed because the Americans were continually bringing new troops into the bridgehead. In addition to three battalions of the 37th SS Panzer Grenadier Regiment, the German units which figured in the Dornot bridgehead fighting were primarily the 282d Infantry Battalion (Battalion Voss), which had been holding the line extending south from the center of the horseshoe woods, the SS Signal School Metz (Battalion Berg), and the 208th Replacement and Training Battalion, all under the control of Division Number 462. (The 3d Battalion, 37th SS Panzer Grenadier Regiment, was apparently in reserve and was not actively committed in this operation.)

[FOOTNOTE 46:] 37th SS Pt Gren Regt Miscellaneous File; MS # B-042 (Krause); MS # B-222 (Knobelsdorff).

" (pages 30-31)

[9 Sep 1944] "The Americans in the bridgehead could take few prisoners. Representative of enemy refusal to surrender was an event in late afternoon of 9 September when approximately a platoon of Germans attacked Company F. Some twenty were killed with automatic rifle and rifle fire close to the defenders' foxholes; about five others dropped behind the bodies of their comrades. Feigning wounds, although still holding on to their weapons, the five would not respond when men of Company F called out for their surrender. Fearing what might happen after dark if the Germans were left so close to the forward foxholes, Company F had no alternative but to shoot them where they lay.

" (page 31)

[9-10 Sep 1944] "A number of times the Germans tried another ruse: while a German officer shouted in English to "cease firing," a group of the enemy would form for a local assault to be launched during the expected lull in American fire. The trick worked only once, and then only partially and to the enemy's disadvantage, when the 1st Platoon, Company E, obeyed the command, only to realize when it was repeated that it was given with a foreign accent. Opening fire again, the platoon wiped out a group of fifteen to twenty Germans who had started an assault.

" (page 31)

[9-10 Sep 1944] "On the west bank an enemy machine gunner, superbly camouflaged in a logcovered, well-sodded emplacement at the north end of the lagoon between the railroad and the river, remained undetected from the day of crossing until 10 September, providing continual harassment to troops at the crossing site. With the muzzle of his machine gun remaining within his emplacement while he fired

through a nine-inch aperture, the German could not be located. Although at night he impudently sang German songs, the American troops still could not find him. His position was not neutralized until 10 September when it was placed under area fire by 60-mm. mortars, automatic rifles, and rifles of Company I, 11th Infantry.

[FOOTNOTE 47:] Colonel Lemmon had no troops to send to clear out west-bank opposition. In answer to a request for such aid, regiment sent either a company or a platoon (probably Company C, 11th Infantry) on this mission, but Colonel Lemmon noted no decrease in enemy fire. Interv with Lemmon; Statement, Capt Stanley R. Connor to OCMH, Jun 50, filed in OCMH.

" (page 31)

[9-10 Sep 1944] "In midmorning of 9 September the Company K commander, 1st Lt. Stephen T. Lowry, was killed in the bridgehead. The one company officer who had not yet been killed or wounded, 1st Lt. Johnny R. Hillyard, assumed command. Just after daylight the next morning, Lieutenant Hillyard too was killed. The 1st sergeant, Thomas E. Hogan, took command of the company.

" (pages 31-32)

[9-10 Sep 1944] "Incidents of individual heroism continued to be almost commonplace. In Company G Pvt. Dale B. Rex took over a machine gun on the left flank when its gunner was killed early on 9 September and manned it through the remainder of the battle. Near-by riflemen estimated that Private Rex killed "wave after wave" of Germans; "hundreds," said the grateful riflemen. In Company K, T/5 William G. Rea, a medical aid man, rendered continuous first aid to the wounded despite machine gun and rifle fire. Once he crawled under fire 300 yards to reach a wounded man, returning unaided with the patient and walking erect through the small arms fire. Almost all officers in the bridgehead were soon either killed or wounded because they moved from their foxholes to encourage their men and direct improvements on the positions. Some men reported that their officers apologized to them for being wounded.

" (page 32)

[8-10 Sep 1944] "The first night in the bridgehead the men dug slit trenches as fighting positions and later improved them, developing what some dubbed "mole holes," a foxhole dug at one end of a slit trench. Because their weapons' fire blasts revealed the defensive perimeter, crews of Company H's 81-mm. mortars abandoned their weapons and took up rifles from the dead and wounded to continue the fight. Even the rifle companies' 60-mm. mortars had to be shifted constantly to avoid revealing positions by fire blast.

" (page 32)

[9-10 Sep 1944] "Communications proved to be a bright spot. Although radio became the sole means of communication, the SCR-300's worked almost perfectly, aided by the proximity of the bridgehead to the battalion command post in Dornot. When Company F's radio was battered by fire and Company G's lost and believed captured, Company F joined in the use of Company K's radio and Company G shared Company E's. One SCR-300, which had been taken across with the men of the 23d Armored Infantry Battalion, had been almost immediately destroyed; but the forty-eight armored infantrymen, reduced to an even smaller number by continuing casualties, were soon virtually integrated into the rifle companies. Adequate replacement batteries for the SCR-300's were supplied satisfactorily at night. Even if the batteries had given out, communications personnel were prepared to switch the battalion SCR-284 to the same frequency as the company SCR-536's. No attempt was made to lay telephone wire across the river, but an adequate net existed on the west bank. A double trunk line from the 2d Battalion to the 11th Infantry command post was shot up so badly that repair was impossible and another line had to be laid. The 2d Battalion also had telephone connections with the 3d Battalion, its own aid station and observation post, and the 23d Armored Infantry Battalion. Although a line was laid the first night from the 2d Battalion CP to the crossing site, it was shelled out so quickly that replacement was not immediately attempted.

" (page 32)

[9-10 Sep 1944] "The 11th Infantry regimental observation post during the action was in a former German bunker atop the hill mass just northwest of Dornot. A forward regimental command post was in another bunker a few hundred yards behind the observation post on the reverse slope of the hill.

[FOOTNOTE 48:] Interv with Morse.

" (page 32)

[9-10 Sep 1944] "The supply performance of the first night was repeated the night of 9 September by men of both the 2d and 3d Battalion Ammunition and Pioneer Platoons, even to manning the assault boats. Supply was under the direction of 2d Lt. Tyrus L. Mizer, 2d Battalion S-4.

[FOOTNOTE 49:] Moselle River Crossing. With the 2d Battalion and Company K in the initial assault went the following ammunition: 5,000 rounds with each light machine gun; 9,000 rounds with each heavy machine gun; and 100 rounds with each 60- and 81-mm. mortar. Transported later were: 1,000 rounds of 60- and 81-mm. mortar ammunition; 60,000 rounds of .30-caliber in machine gun belts; 13,000 rounds of .30-caliber in 8-round clips and 6,000 in 5-round clips for BAR's; 200 antitank "bazooka" rockets; 200 rifle grenades; and 200 hand grenades.

" (page 33)

[9-10 Sep 1944] "The combined 2d and 3d Battalion aid station, under Capt. John M. Hoffman, 2d Battalion surgeon, Capt. Emanuel Feldman, assistant regimental surgeon, and Capt. Panfilo C. Di Loreto, 3d Battalion surgeon, continued to operate in the cellars of Dornot. To assist evacuation, a casualty relay point was established, shifting from the railroad underpass to the first house in the eastern edge of Dornot according to the vagaries of enemy shelling. Enemy fire was usually so heavy at the crossing site in daylight that litter bearers could not remain in the vicinity. Although medics made occasional trips to the site, many wounded had to make their way back alone as far as the railroad underpass. At approximately 2300 the night of 9 September, four men of Collecting Company C, 5th Medical Battalion, crossed by boat to the east bank, collected casualties from the bridgehead, and returned. As they were preparing to enter the boat for a second trip, a round from an enemy tank blew the craft from the water. Although infantrymen and aid men continued to get their wounded comrades across, theirs was the last actual evacuation from the bridgehead by west-bank medics.

[FOOTNOTE 50:] T/5 Gearhart, T/4 George C. Berner, Sgt Leo W. Phelps, and Pvt Ernest A. Angell. [The four men of Collecting Company C, 5th Medical Battalion.]

" (pages 33-34)